The Sectarian Solution

The Sectarian Solution

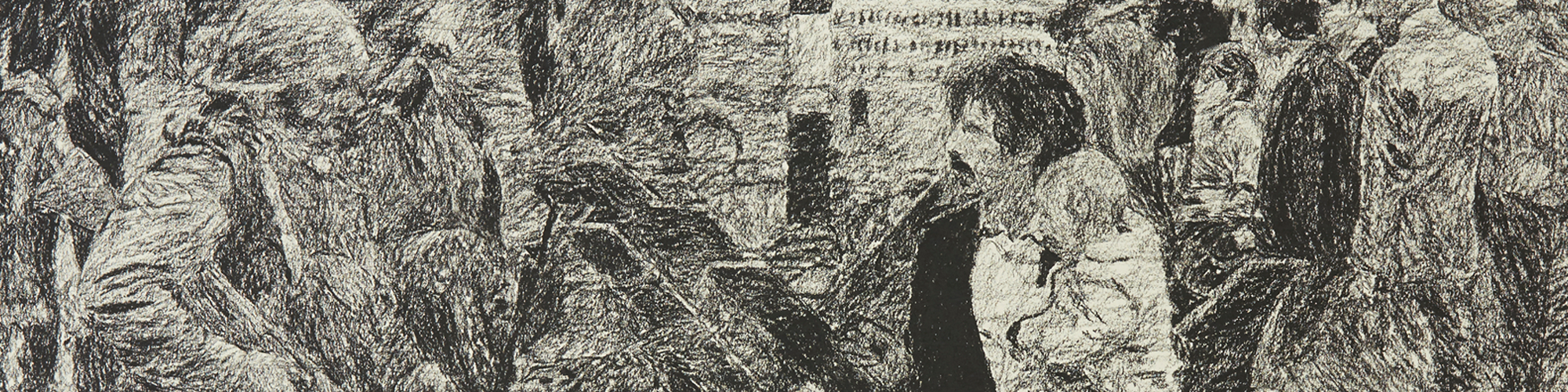

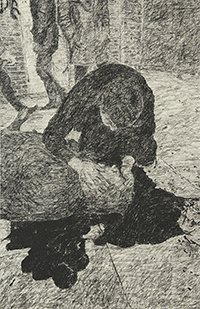

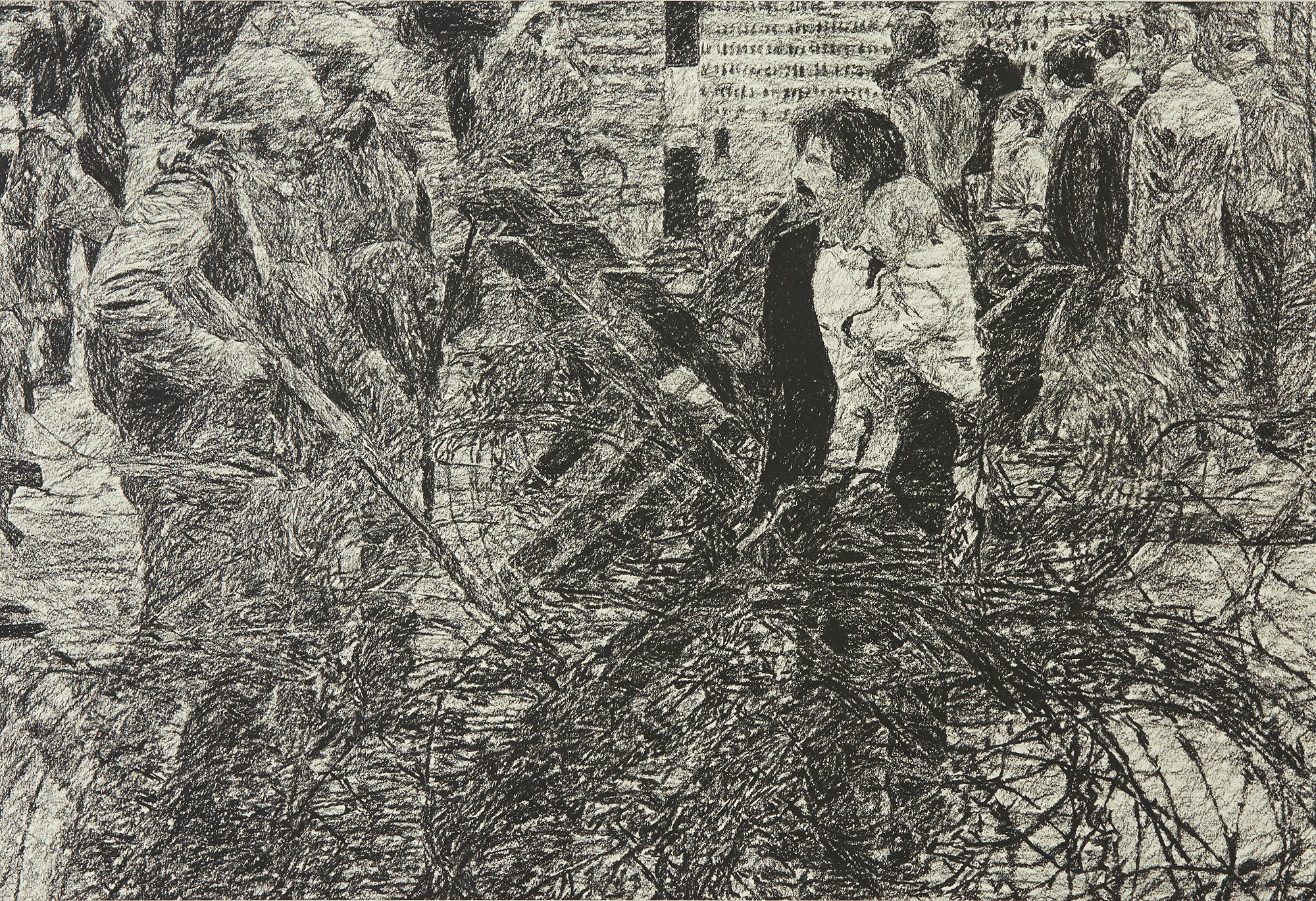

In August of 1969 Bombay Street in Belfast, a Nationalist area near the interface of the Falls Road area and the Unionist Shankill road area, was burned to the ground by a Loyalist mob. Taoiseach Jack Lynch condemned the RUC’s actions during the riots in Derry and Belfast on television. Lynch stated that the Irish government could no longer stand by and see innocent people injured or killed. Lynch called for the United Nations to deploy a peacekeeping force and stated that the Irish Army would establish field hospitals in Donegal near the border close to Derry. Lynch also stated that the only permanent solution would be the end of partition. Following the riots, Lynch had ordered the Irish Army to plan for a potential humanitarian intervention in the North of Ireland, but the plan was never executed and kept classified for decades.

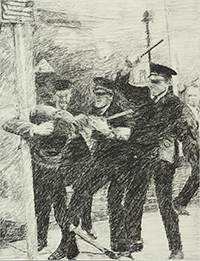

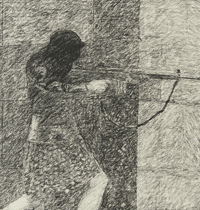

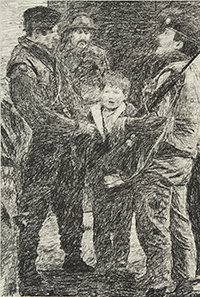

In 1969, British troops were deployed on the streets of Northern Ireland. The troops were sent to restore order and were initially welcomed by the Nationalist community who were distrusting of the RUC. That year the first of the “peace lines” separating Nationalist and Unionist communities were erected in Belfast as temporary structures intended to last only six months. The objectives of the British military switched from protecting the people to implementing a counter-insurgency campaign. The relationship between the British and the Nationalist community rapidly deteriorated. A series of events involving British soldiers and Nationalist civilians led to the view that the army was no less discriminatory than the RUC.

In July of 1970 the British Army began a campaign of weapons searches in the Nationalist Falls Road area which led to skirmishes between local youths and the troops. The troops fired CS gas, which was followed by hours of gun battles with the IRA. The British Army sealed off the area comprised of 3,000 homes and implemented a curfew. British troops numbering in the thousands marched into the area and carried out house-to-house searches. A large amount of CS gas was fired and there was significant destruction to the neighbourhood. Several residents complained of abuse by the soldiers. Thousands of women and children from the Nationalist community of Andersontown marched into the the curfew zone with groceries and food for the residents, ending the curfew. At least 78 civilians were injured and four were killed by British soldiers, 337 people were arrested, 18 soldiers were injured, and it was later admitted by the British Army, that some of its troops were involved in looting.

In 1971, the British government implemented a policy of internment without trial. 1,981 individuals were interned between 1971 and 1975, of those interned, only 107 were Loyalists. The British Army classified the period as the insurgency phase of the conflict. The rates of violence against Nationalists by the British troops were high. 170 people, many of whom were civilians, were killed between 1971 and 1974. A number of incidents against unarmed civilians were recorded such as the Ballymurphy Massacre with 11 killed, the Springhill Massacre with 5 killed, and Bloody Sunday with 14 killed.

One of the few moves by the British military that seemed to have any success at reducing violence between communities was the creation of “peace lines”. Although when the “peace lines” were constructed in 1969, they were intended to stand for six months, they only grew. The lines became longer, wider, and higher; they were also constructed in a more permanent manner. The majority of the lines were constructed in Belfast. The most well recognised of these walls divides the Nationalist Falls Road area from the Unionist Shankill Road area in West Belfast. Walls were also constructed between the Nationalist Short Strand area and the Unionist Cluan Place area of East Belfast, the Nationalist Bishop Street area from the Unionist Fountain Estate in Derry, and the Nationalist Orbins Drive and the Unionist Corcrain Road in Portadown. Over the years the walls have multiplied from about 18 in the early 1990s to roughly 59 as of 2017. In total the lines span more than 21 miles and have increased in height following the Good Friday Agreement, leaving the Northern Irish state a literally and figuratively divided society.

The Sectarian divides in the North of Ireland are deeply entrenched. Education has been largely segregated. About 90 percent of children go to separate schools by faith. Many children may go from age 4 to 18 without much experience with children from the other community. Only since the mid 1990s has the British government implemented laws that seek to prohibit discrimination in employment and investigate allegations of such discriminatory practices in organisations and businesses in Northern Ireland. During “The Troubles” many cities became self segregated. In 2004 it was estimated the more than 92 percent of public housing in Northern Ireland is divided along religious lines; the percentage in Belfast was as high as 98 percent. In 2005 it was estimated that more than 1,400 people were forced to move as a consequence of intimidation annually. Between 1970 and the 1990s, a mere five percent of marriages in the North of Ireland crossed community lines. A 2005 survey taken in interface areas between communities in cities like Belfast found that 75 percent of respondents refused to use services nearest to them due to location, 60 percent refused to shop in areas dominated by the other community, and 82 percent frequently travelled to areas they perceived as safer for services even when it was farther out of their way.