“The Troubles”

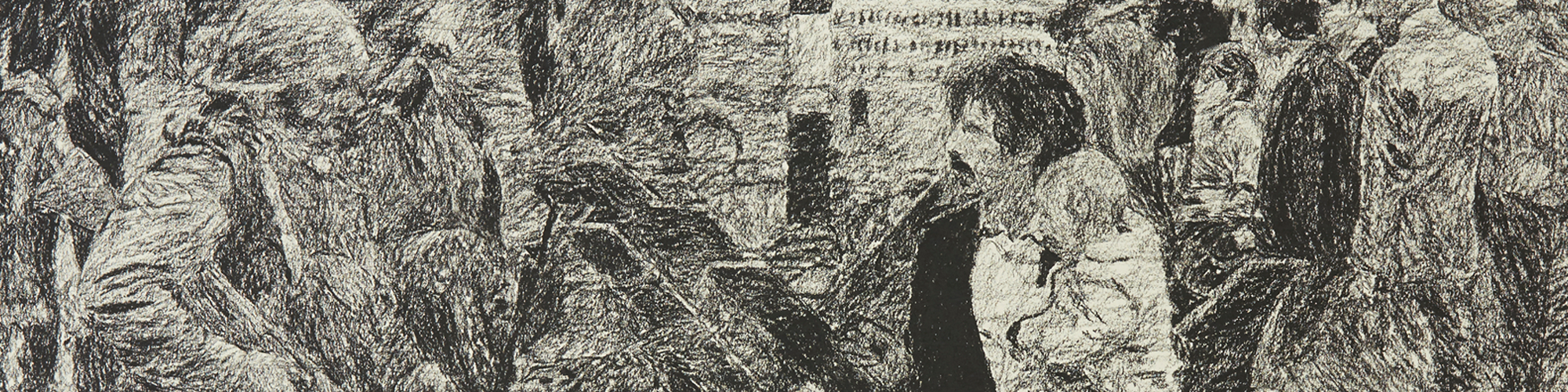

The following is a collection of twelve works in charcoal based on images from The Troubles. As an anthropologist, the artist created the collection to be a combination of images and information. As a gallery, the collection is meant to employ art as an immersive learning experience. There is an introduction to the history behind The Troubles to assist in the immersion process. Each work is also paired with a passage that provides additional information as a journey through the conflict itself. The initial conceptualisation of the collection began in 2016, the centenary of the Easter Rising, 35th anniversary of the 1981 Hunger Strikes, and 15th anniversary of the Holy Cross Dispute. The works themselves were completed between June and September of 2017 and were intended to be viewed as a complete collection. Although the gallery is meant to be viewed in its completion, the artist also welcomes anyone who simply wishes to enjoy the visual component of the collection.

Introduction and Background to The Troubles

The Troubles is a label used to describe an era of violent ethno-political conflict in the North of Ireland between the late 1960s and early 2000s. The earliest roots of the conflict go back roughly 800 years to when English colonialism first began in Ireland. Ireland as a whole experienced little peace and drastic changes through cultural conflict and evolution from this point onward. There were nearly twenty significant and well documented Irish uprisings between 1500 and 1900. England’s treatment of the Irish people was brutal as they struggled to supress the Irish population and their culture. During Oliver Cromwell’s conquest of Ireland, conservative estimates place the death toll at 220,000 for the Irish with around 50,000 forcibly deported as indentured labourers. Some historians estimate that Ireland’s population may have dropped by as much as 80 percent. Between 1740 and 1741, the economic policies of English landlords cause 400,000 Irish deaths by starvation and more than 150,000 Irish to emigrate.

At the end of the 1700s a new form of cultural evolution in Ireland was taking shape. Individuals of English descent who had spent their whole lives in Ireland began to see themselves as Anglo-Irish. The descendants of the Scottish Plantation of Ulster underwent a cultural evolution and would eventually define themselves as Ulster-Scots. Much like the Norman invaders centuries earlier, these unique groups from other lands began to see Ireland as their homeland. The Irish Rebellion of 1798, led by Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Protestant of French descent, was inspired by the French and American Revolutions of that period. The rebellion grew from the Society of United Irishmen which initially formed from a group of Protestants in Belfast and quickly crossed religious divides. The rebels had goals of emancipating Catholics, breaking from England and taking more local control over Ireland, and moving toward a more secular form of government. Although the rebellion failed, it was significant as it laid the foundation for the future struggles that Ulster would face. The union across religious divides during the rebellion proved that the divisions of Irish society were more a product of power dynamics and ethno-political categorisation as opposed to religion.

In 1800, the Acts of Union created a new entity called the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Irish Catholics, who constituted the majority of Ireland’s population, still struggled to gain rights. In 1832, a Catholic attorney named Daniel O’Connell succeeded in a goal of Catholic emancipation and a seat in Parliament. Despite the political changes, conditions for the Irish under British rule were still dismal. The British government and Anglo-Irish landlords imposed strict policies against the Irish as a blight afflicted potatoes, a vital food source for the Irish between 1845 and 1849. Charles Trevelyn, a British colonial administrator in charge of government relief, severely restricted aid to the Irish. Trevelyn viewed the crisis as an act of god sent to rid British lands of an inferior people, stating, “God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson”. Between 1841 and 1851, the population of Ireland dropped from 8,175,124 to 6,552,385, emigration during and after this period resulted in the population dropping to only 4.4 million by 1911. Through British policies, death, and emigration, the Irish language was nearly destroyed. Since colonial policies and Anti-Irish sentiment were responsible for the losses in population and culture, the era falls under The Hague Convention of 1948’s definition of genocide. This period fuelled the resurgence in Irish republicanism that would eventually lead to the end of British rule over most of Ireland.

The Easter Rising of 1916 paved the way to the Irish War of Independence. Irish independence was only realised in 26 of the 32 counties. In 1921 Ireland was partitioned; six of the counties in Ulster were to remain a part of the United Kingdom known as Northern Ireland. In the Irish Free State, there was a civil war between 1922 and 1923. Republicans who strongly opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the partition of Ireland, which they saw as a betrayal of the Irish Republic, fought against the newly formed Free State government. The Anti-Treaty IRA had a strong presence in Munster and burned the homes of the land owning Anglo-Irish aristocrats. This caused many Anglo-Irish Protestants to leave the Irish Free State and fuelled the anxieties of the Anglo-Irish Protestant population of Northern Ireland. In 1949, the Irish Free State was declared a republic and left the British commonwealth. The Special Powers Act of 1922 granted the government of Northern Ireland the power to do nearly anything it deemed necessary to re-establish order. The act was used heavily against the Irish Nationalist community, increasing tensions between ethno-political groups. Under the act, police were allowed to search without any warrants, imprison individuals without charges or trials, ban publications, and ban parades or other assemblies.

The foundations of sectarianism in the North of Ireland were well established even before partition. While the Special Powers Act banned assemblies and parades for Nationalist communities, it allowed Unionists to exercise the rights Nationalists were denied. The Orange Order, a fraternal organisation established in 1798 to maintain the Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland, is one of the best examples that serves to highlight the inequalities in the rights of assembly and public demonstration. The Orange Order celebrates the Dutch-born Protestant king William of Orange and his victory over James II, the Catholic king of England, in the Williamite-Jacobite war at the Battle of the Boyne with their parades on the 12th of July. The “Twelfth” parades were often routed through Nationalist areas as a means of reinforcing the idea that the Protestant Ascendancy is still in full strength. The Orange Order views itself as a defender of Unionist and Protestant civil and religious liberties, but the organisation is frequently criticised as being triumphalist, supremacist, and sectarian. With many politicians and members of the RUC as members of the Orange Order, coupled with its frequent parades through Nationalist areas, Northern Ireland was seen as an Orange state that was rooted in sectarianism.

As Irish Nationalists/Republicans began to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising in 1966, the Unionist/Loyalist community in the North feared that there would be another campaign to unite Ireland. An Irish Republican group destroyed Nelson’s Pillar in Dublin, a monument seen as a symbol of British colonialism by Republicans. The attack on Nelson’s Pillar helped fuel Unionist anxieties that Irish republicanism would threaten the existence of Northern Ireland as a state. In April of 1966, Ian Paisley, a fundamentalist preacher, led Loyalists in founding the Ulster Constitutional Defence Committee (UCDC). It established a paramilitary style wing named the Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV). Their goal was to oust the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Terence O’Neill, who they thought was too soft on the growing Irish civil rights movement. During this time a Loyalist paramilitary group called the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) began in the Shankill area of Belfast under the direction of a former British soldier named Gusty Spence. Many members of the UVF were also involved in the UPV and UCDC. In April and May, the UVF petrol bombed a number of Catholic schools, businesses, and homes.

In January of 1967 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was formed. Along with other civil rights groups, the NICRA began a non-violent civil rights campaign. The campaign’s stated goals were: to end discriminatory housing allocation, end the policy that only individuals that owned households could vote in elections, end gerrymandering, end job discrimination, reform the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and repeal the Special Powers Act. The civil rights movement’s first march occurred in August of 1968. These marches were met by attacks from Loyalists and inaction from the RUC in protecting the marchers from attackers. In October, the government banned a civil rights march in Derry. The civil rights movement defied the ban and was attacked by the RUC with more than 100 injured. The event sparked riots in Derry. On the first day of 1969, a civil rights march from Belfast to Derry was held. At Burntollet Bridge, a group of roughly 200 Loyalists, including off duty members of the RUC, armed with bottles, bricks, and iron bars attacked the protesters in a move that was planned in advance. That evening, members of the RUC went on a rampage through the Nationalist Bogside area of Derry. Bogside residents barricaded the neighbourhood to keep the RUC out, creating an area known as “Free Derry”.

In August of 1969, British soldiers were deployed in Derry and Belfast. Many Nationalists welcomed the troops at first because of their distrust and fear of the RUC. Although the troops were deployed to restore order, violence and paramilitary activity increased. The Provisional IRA and the more Marxist Official IRA formed as the IRA split into two factions in 1969. In 1970 a curfew was imposed by the troops in the Nationalist Falls Road area of Belfast. In 1971 a policy of internment without trial was instituted. Initially, approximately 350 were detained; none were Protestant. Most of the detainees were not Republican activists, but were subsequently radicalised by their experiences. The government, with its policy of internment, served as the single largest recruitment factor for the IRA. 1972 had the highest rates of violent conflicts during The Troubles. Almost 500 people were killed, at least half of them were civilians.

Bloody Sunday was the most widely know incident during The Troubles. On the 30th of January 1972, thirteen unarmed civilians were shot dead at an anti-internment march in Derry. A fourteenth man died of his injuries months later and many more were wounded. In the wake of Bloody Sunday, hostilities between the Provisional and Official IRA and the British army increased dramatically. 1,981 individuals were interned between 1971 and 1975, of these, only 107 were Loyalists. Allegations of abuse and torture of detainees were widespread. The “five techniques” of interrogation, which included food, drink, and sleep deprivation, used by the British military and police in Ireland were declared illegal after an inquiry in 1972. British troop concentrations reached as high as 20 soldiers per 1,000 civilians. This was the highest ratio in the history of counterinsurgency warfare.

Republican prison protests in the late 1970s and early 1980s marked the beginning of a shift in the conflict. In 1976, the British government ended Special Category Status for Republican prisoners, which classified them as political prisoners and granted them some of the privileges of POWs under the Geneva Convention. This meant that Republican prisoners would be categorised and treated as criminals. In September of 1976, a Republican prisoner named Kieran Nugent refused to wear a prison uniform and wore only the prison blanket as clothing, starting the Blanket Protest. The protest was met with hostility and no compromise in policy, leading to increased hostilities between guards and prisoners as well as riots. The Blanket Protest led to a no-wash protest by 1978 as prisoners were left in cells 24 hours a day with only mattresses and blankets and with nowhere to empty their chamber pots. Under the command of Brendan Hughes, Republican prisoners commenced a hunger strike in 1980. This strike lasted 53 days, ending before the death of participant Sean McKenna who was slipping in and out of a comma. Hughes decided to end the strike when the government sent a document detailing a proposed settlement, but the prisoners’ demands were not met.

The 1981 Hunger Strike led by Bobby Sands resulted in Sands being democratically elected as a member of British Parliament. In response to his election, the British government introduced the Representation of the People Act 1981, which barred prisoners in both the UK and Ireland from candidacy in elections. This move signalled that the British government felt seriously threatened by Republicans moving from violence to democratic tactics. The strike was a direct showdown between the prisoners at Maze Prison and British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. Sands died after 66 days on hunger strike. Ten other prisoners following Sands on hunger strike died as Thatcher and her government refused any form of negotiation or compromise. The strike gathered the world’s attention to the conflict in the North of Ireland and led to the emergence of Sinn Féin as a mainstream party. The strike did not accomplish its primary goals, but it was a significant Pyrrhic victory for republicans. International response and support for the strike was massive. The USSR condemned Britain, students in Milan burned British flags, the British consulate in Ghent was raided, protestors in Oslo threw a tomato at Queen Elizabeth II, and there were riots at the British embassy in France. Iran officially renamed the street on which the British embassy was located in Tehran from Winston Churchill Street to Bobby Sands Street and streets in numerous cities in France and in New York were also renamed after Sands. Memorials to Sands and the Hunger Strikers exist across the world from Cuba to Australia.

Although violence between the British military and the various paramilitary groups persisted through the 1980s and 1990s, political moves were being made to arrange the end of the conflict. A ceasefire was arranged in 1994; while it ultimately fell apart, it set the stage for ceasefires to come. In 1995 the United States appointed George Mitchell as a Special Envoy for Northern Ireland under the Clinton administration. The Irish and British governments agreed to let Mitchell chair an international commission for the disarmament of the various paramilitary groups. The British refused an all party negotiation for total disarmament until the IRA decommissioned its weapons first. The IRA revoked the ceasefire in February of 1996 and bombed the Canary Wharf area of London, followed by more attacks, the most significant of which was in Manchester. The Manchester bombing was the largest bomb attack in Britain since the Second World War, but a telephone warning preceding the attack prevented any casualties. The IRA reinstated their ceasefire in July of 1997. In September, Sinn Féin was admitted to the talks for the Good Friday Agreement.

The Good Friday Agreement was an agreement between the Irish and British governments and Sinn Féin, the Ulster Unionist Party, the Social Democratic and Labour Party, the Alliance Party, Labour, the Progressive Unionist Party, the Ulster Democratic Party, and the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition. The agreement recognised the views of both Unionist and Nationalist groups, but left the future sovereignty over Northern Ireland open-ended. The agreement maintained that Northern Ireland is a part of the United Kingdom until such time that the majority of the people in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland vote otherwise. The people of Northern Ireland were given the right to identify as and hold citizenship as Irish, British, or both. The Democratic Unionist Party was the only major political group to oppose the agreement. The agreement led to the decommissioning of arms by paramilitary groups and the normalisation of security arrangements in the North of Ireland. The Good Friday Agreement is regarded as the endpoint of The Troubles, but the North of Ireland is still in a state of conflict transformation today as it navigates its way into the future with reconciliation and non-violence.