Lessons Learned in Ardoyne

Lessons Learned in Ardoyne

In 2001 and 2002, a series of events referred to as the “Holy Cross Dispute” occurred in Ardoyne, an area in North Belfast. As the city of Belfast became increasingly segregated during “The Troubles”, fiercely territorial disputes occurred. Ardoyne is a primarily Nationalist area with a small Unionist enclave, Glenbryn. Holy Cross, a catholic primary school for girls was left within the Unionist enclave as the area residents became segregated. While the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, political tensions remained high. With Ardoyne being a heavily divided area that was also economically deprived, it made for a volatile environment as dissident Republican and Loyalist groups continued small-scale campaigns of violence. Residents from both communities complained that their homes were subjected to sectarian attacks.

On the 19th of June 2001, two young UDA men raising Loyalist flags along Ardoyne Road ahead of the Unionist marching season, claimed that a car full of Republicans drove into their ladder, provoking a riot. According to a Loyalist resident of Glenbryn who witnessed the event, Gail Blundell, the UDA men’s account was a lie. Blundell stated that as parents started to arrive to collect their children at Holy Cross that afternoon, the car in question drove on and the UDA men threw the ladder at the back of the car. The men in the car got out and a fight started immediately. The children of Holy Cross school and their parents became the target of riots and protests that became increasingly vicious. Loyalists argued that the children were used as cover while the parents made intelligence runs for attacks on Loyalist homes. Loyalist anxiety was a factor in the escalation of events. The Nationalist side of Ardoyne was thriving and overcrowded, whereas the Unionist community was losing its numbers as residents moved out of the area. The police refused to release any comparative crime figures from Ardoyne and Glenbryn, arguing that the police would not place blame on either side. Yet, that summer, Assistant Chief Constable Alan McQuillan was given intelligence that UDA members had bombs and arms and planned to exploit tensions within the community to kill police officers and Nationalists.

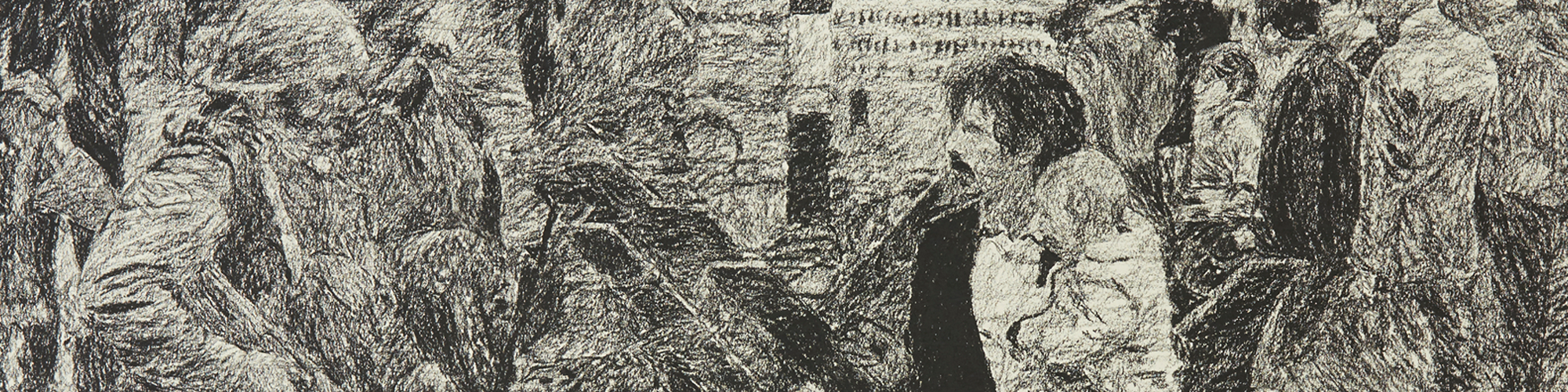

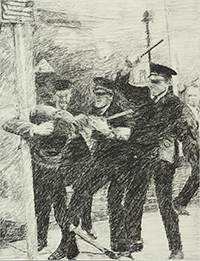

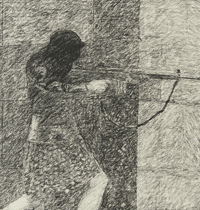

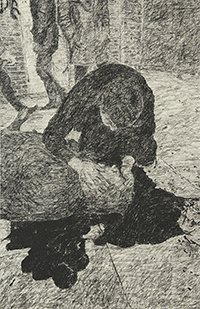

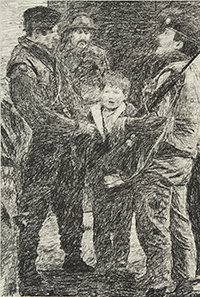

Hundreds of Loyalist protestors picketed and blockaded the walking route to Holy Cross. The picketing started in June, ceased as the school let out for summer, then resumed when school resumed, from the 3rd of September to the 23rd of November. Abusive sectarian insults, such as “fenian whores”, were shouted at the children. Bricks, stones, fireworks, balloons filled with urine, and blast bombs were thrown at the children and their parents. Riot police numbering in the hundreds, aided by British soldiers, had to escort the children and their parents to and from school through a hostile gauntlet. One Loyalist paramilitary group, the Red Hand Defenders, made death threats to the staff and parents of Holy Cross. Parents and children were violently stoned and the riot police were attacked. One Sinn Féin leader, Gerry Kelly, who played a leading role in negotiations for the Good Friday Agreement, compared the incident to protests by white supremacists in Alabama during the 50s and 60s.

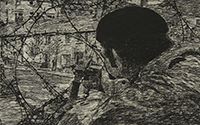

Community leaders on either side were unable to prevent the situation from escalating. Riots broke out at night. Acid bombs, bricks, blast bombs, bottles, and petrol bombs were thrown and firearms were discharged injuring officers. On the evening of June 21st, Loyalists threw 46 petrol bombs and six blast bombs at the police. On the sixth week of the protests, after they resumed in September, the cost of policing the protest reached £1 million. On November 7th, Desmond Tutu, a religious leader known for his anti-apartheid and human rights activism, met with some of the children and their parents. Although Tutu was an Anglican Archbishop, Protestant church leaders did not support him, and some were severely opposed to his visit to the children. Although the protest was broken by the 23rd of November, police and British army maintained an armoured presence outside the school and the nearby intersection every day for a number of months.

Another set of large scale riots occurred in January of 2002. Parents and children were once again under attack. 130 improvised bombs were thrown, four Nationalist youths were hospitalised from shotgun pellets, Nationalist homes were attacked, Loyalists petrol-bombed and destroyed a police vehicle, and a few people were hit with cars. 400 police officers and soldiers were deployed to stop the violence. 14 officers were injured in the first day alone. Holy Cross was forced to close. A group of six Loyalists, one armed with a gun, commenced an attack through the grounds of Our Lady of Mercy, a Catholic girls’ secondary school. 18 cars were smashed with crowbars. The Red Hand Defenders issued another set of death threats. Two Catholic schools were the subject of arson attacks and teachers at the schools had their cars attacked. 750 armed officers and soldiers were dispatched to protect the area schools and armoured vehicles lined Ardoyne Road. Eventually the riots ended.

Catholic schools in Ardoyne have remained sites targeted by Loyalists. In 2003 a pipe bomb was placed at the school’s entrance, but was defused with no fatalities or injuries. In 2013, Loyalists painted kerbstones at the entrance of the school the colours of the British flag. They also mounted British and Loyalist paramilitary flags outside the school. The Police Service of Northern Ireland had to stop a Loyalist protest that was fuelled by fabricated rumours on social media that the government would remove the flags. In April of 2017, a police patrol discovered a bomb outside the gates of Holy Cross Boys’ Primary School in Ardoyne.

Enrolment at Holy Cross Girls’ Primary School nearly dropped in half following the protests. The head of the Survivors of Trauma group, Brendan Bradley, noted that the level of trauma experienced by the children was nearly without comparison by any other event during “The Troubles”. The trauma went on for months, with some of the girls being as young as four at the time. Many of the children were placed on heavy tranquilizers due to their re-experiencing the trauma. Although the event is sometimes referred to as one of the darkest during “The Troubles”, it is important to note that the incidents occurred fours years after the Good Friday Agreement. The Holy Cross dispute erupted after peace had been negotiated, serving as a reminder that disarmament did not end sectarianism.